Discourse Explainer: the scale of American education

The Buffalo and Erie County Public Library's semi-annual used book sale was last week and much to my delight, the tables of old non-fiction books were fairly undisturbed when I got there. How old you ask? So old, most of the books had a version of this affixed to the inside of the back cover.

The sale was crowded but I picked the right starting point and found the philosophy slash education slash literature section and these four beauties pretty quickly.

- The Compounding of English Words: When and Why Joining or Separation is Preferable (1891) by F. Horace Teall

- Educational Aims and Efforts: 1880—1910 by Sir Philip Magnus (which, I discovered when I got home is about English education history.)

- The Support of Schools in Colonial New York by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (1913) by William Webb Kemp

- Our National System of Education: An Essay (1877) by John C. Henderson, Jr.

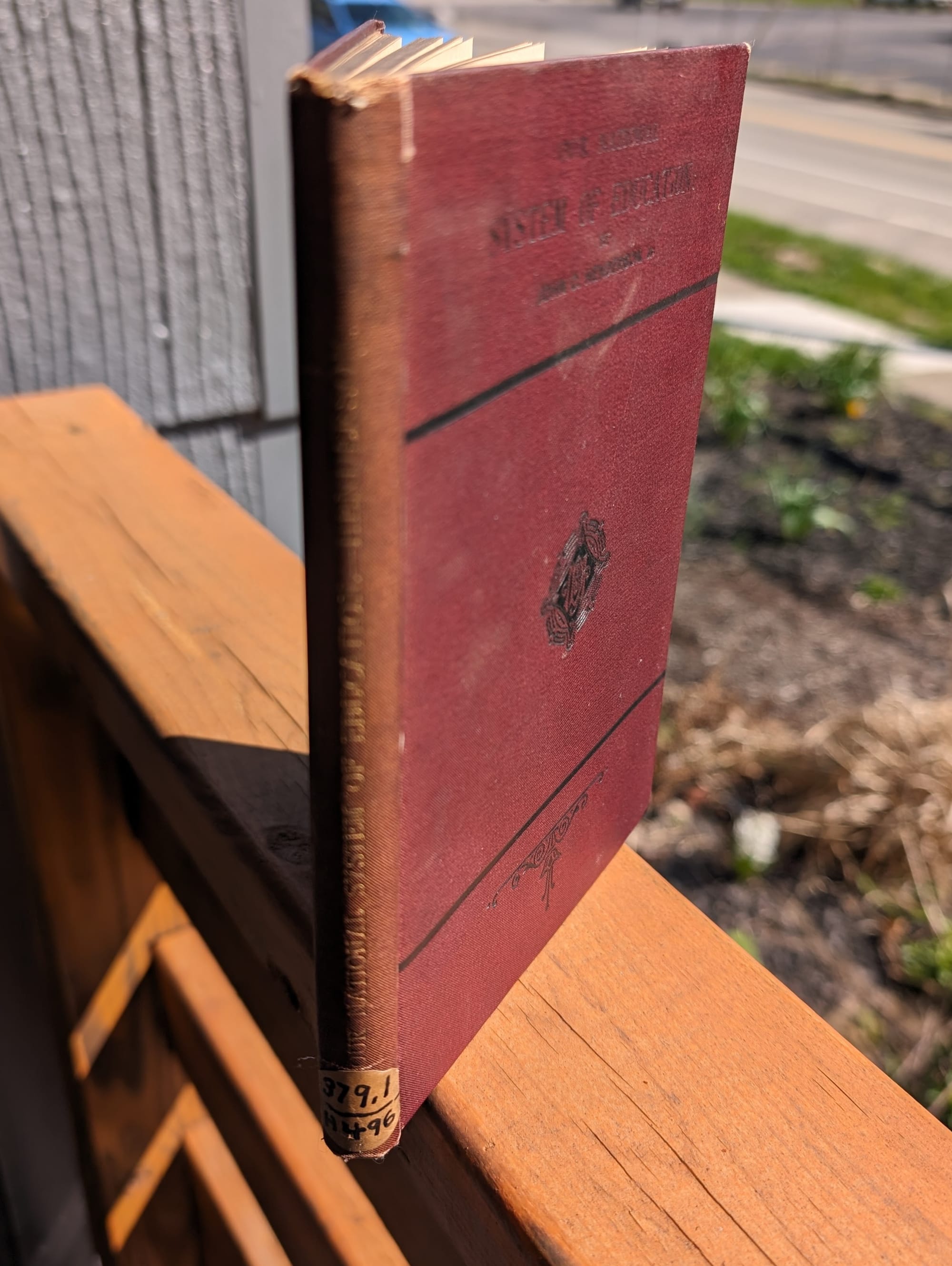

The last one elicited an actual out loud gasp because I'd almost missed it. It was tucked between two larger books with beautiful unmarred spines and just ahead of me, someone who I suspect was an interior decorator was filling a large cart with books selected for what seemed to be aesthetic purposes. Henderson's essay is a slim book, marred by a catalogue sticker. This is going to be an image heavy newsletter but I cannot resist sharing this beauty.

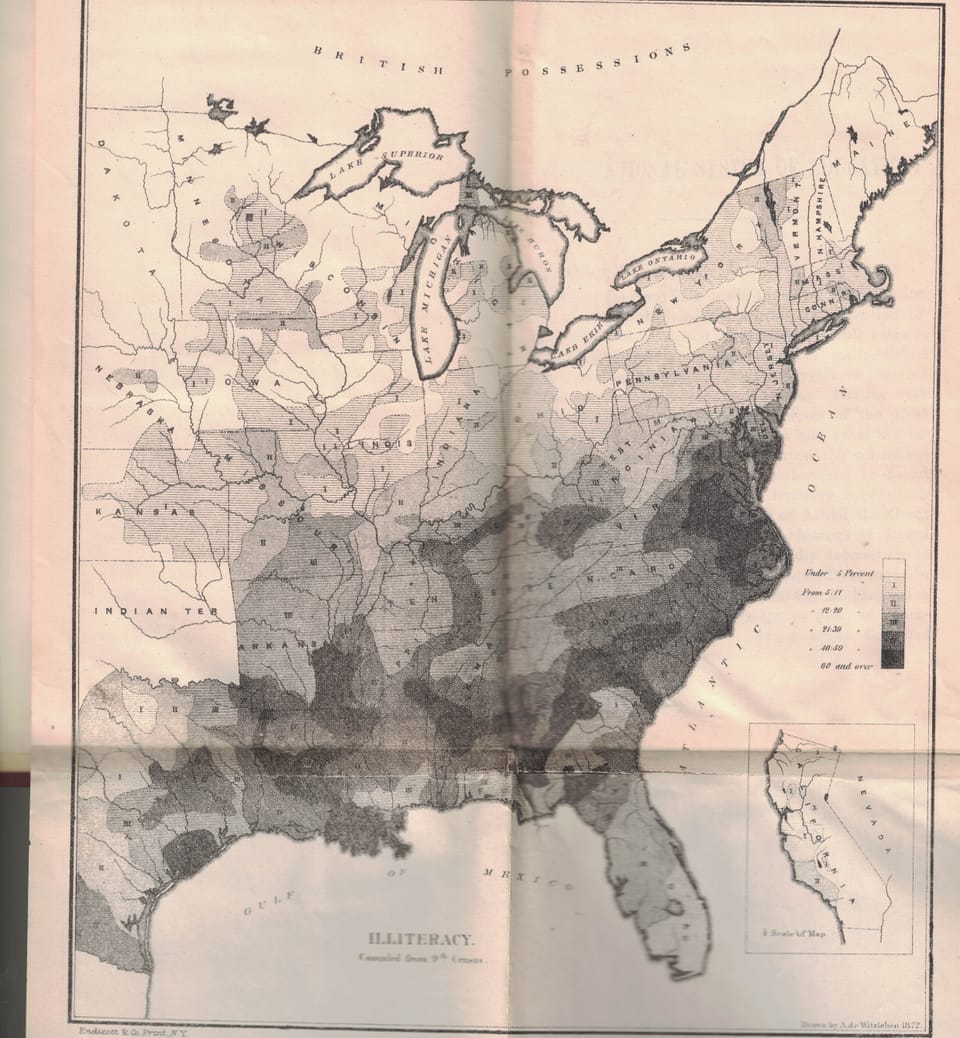

I haven't been able to find out anything about the author; a man with his name lived in Staten Island, owned an estate, and buried a son around the right time. I'm adding "find out more about this dude" to my to-do list but my hunch based on some of the book's contents is that he was a white man of means with access to lots of free time and books. As such, the essay is fairly typical for its time and type. It's a little bit history, a little bit persuasive essay, a whole lot of appendices and a great deal of admiration for the Founders. The essay is housed here at the HathiTrust but is unfortunately missing the beautiful map seen in the picture at the top - one point for Team Physical Copies of Books.

One of the details that make the book so compelling is his earnest belief that America will have, or at the time of his writing has, a national education system. After all, one of his heroes, Thomas Jefferson, was an advocate and every great people and civilization, including "the Mussulmans," established one. There is also his disdain for laws that insist on segregated education. From page 71:

The school-laws in some the States should be amended. For instance, a clause in the constitution of the State of Tennessee reads thus: "No school established or aided under this section shall allow white and colored children to be received as scholars in the same school." Whatever benefit a certain class of people think is secured by forbidding, under any circumstances, the teaching of colored and white children in the same school, such a prohibition, betraying race prejudice, ought not to be in a constitution of any State of the Union.

There's even a section where he bemoans the lack of higher education for women. Not only is it helpful to have yet another example of a white American in history who - using the standards of his time - recognized racism, sexism, and segregation is wrong, Mr. Henderson's earnest optimism about American education is a counter-balance to the cynicism and scorn that seems so present these days. It's delightfully easy to get lost in his prose and I hope you'll check it out.

American Education Then and Now

Shortly before Henderson's essay was published, as explained in one of the last footnotes, the United States House of Representatives debated a bill that would have used the sales of public lands to fund "the education of the people" across the country. A previous attempt had been voted down 103-107 so the authors of the 1877 bill got support from every state-level education superintendent or commissioner and changed the language to link state literacy levels to funding. According to Henderson, the plan was to put it up for another vote in the next year's Congress.

I don't know how that vote turned out. To be honest, I don't want to know. The arguments from the lawmakers defending the bill are so earnest, so based in education as a civil right for Black Americans and to patriotism for all Americans, I don't want to scroll through the 1878 Congressional Record and find out they lost again. So, I'll save that - and more of the history around for another time.

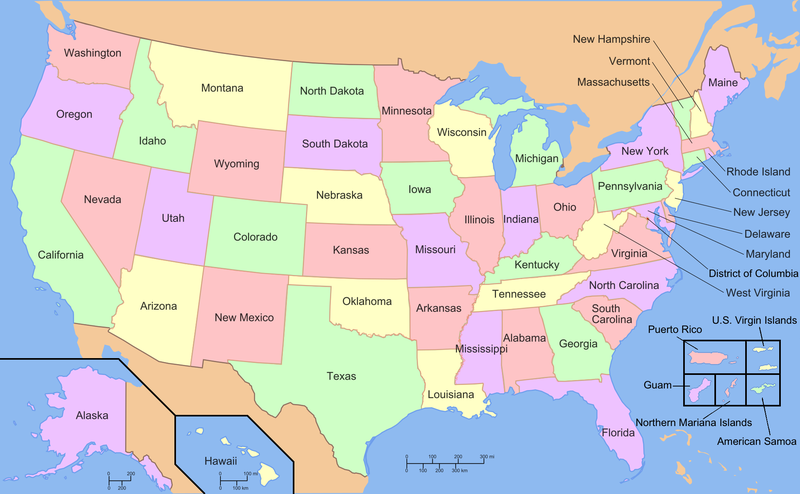

Instead, I'd like to use Mr. Henderson as a proxy for how we think about the scale of the American education system. In 1877, there were 38 states. In the majority of those states, the state-level school system was a loosely cobbled together network of poorly maintained schoolhouses where a teacher, likely only a few years older than her oldest students. (I highly recommend Jonathan Zimmerman's research and the 23 Myths About the History of American Schools: What the Truth Can Tell Us, and Why It Matters for more education in Henderson's lifetime.) Some of the large east coast cities had bureaucracies but they were fledgling and still taking shape. To Mr. Henderson, the American education system was akin to the night sky: thousands of dots scattered across the landscape, with an occasional visible constellation, and a few larger bright spots, mostly over on the right-hand side.

146 years later, we tend to think of American education less like the night sky and more like this: one big system with 50 million students, 3.5 million teachers, and 5 million adults who perform all of the jobs necessary for running schools.

There's a few issues, though, with this mental model. While there is a cabinet-level position for the head of the United States Department of Education, we do not have a national system of education. (As an example of what this means, when Congress passed No Child Left Behind in 2001 which mandated Math and ELA testing in grades 3-8 and once in High School, the law could not mandate which tests to use. So, each state had to design their own.) Unlike many other countries around the world, the federal government has a severely limited say in what happens at the school level when it comes to curriculum, standards, and instruction. Some of this is due to the 10th Amendment and some of it just timing: most of the Northern states had public school systems up and running while most Southern states didn't even start until after the Civil War. So, we need to remember the lines.

That's not even the whole picture, though. Not only are there 56 separate systems of education, also included within the American education system are the 163 Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) schools spread across the country and around the world and the 180 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Education schools across the US and on/in native nations, reservations, and territories. That's 58 separate systems.

But wait! There's more.

Contained within each of these 58 systems are individual school districts (known as divisions in some places.) The IES, the federal agency responsible for collecting statistics in education, reports there 19,253 public local educational agencies in these United States. We're notoriously bad as human beings at conceiving of large numbers so here's what that looks like.

The bunch of rocks that were added after the first pour? That's the 2116 districts in the state of California. 13,000 of these 19,253 rocks are school districts (also known as divisions in some states.) The other 5000 or so are regional and state-operated agencies and schools within the state. These districts, divisions, intermediary agencies, specialty schools are more are known as local education agencies or LEAs.

Each rock represents one of the LEAs in the 50 states, Washington DC, Department of Defense Education Activity schools, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands, Northern Marianas, and tribally-controlled schools supported by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Remember, though, the lines I mentioned above? It's actually more like this.

Those 19,000 rocks have now been redistributed to their own jars. To give a better sense of scale, I dropped rocks representing the three largest districts in the United States: New York City Public Schools, Los Angeles Unified, and City of Chicago SD 299 (also known as Chicago Public Schools.)

Or, if you prefer:

Each rock in each jar represents a school district in the state (or territory or organization.) Hey! Thanks for asking about different colored lids and stones! I'm happy to explain but first, check this out.

Hawaii (on the left) has the same population size as New Hampshire (on the right.) The Hawaiian state constitution established one state-wide school district - every school in the state belongs to the same school district. NH checks in with 300 districts and agencies in the state. Same population. One state has one district, one has 300. New Hampshire has the same number of residents, but 299 more superintendents than the state of Hawaii.

Meanwhile, Texas has a population that is 22 times larger than New Hampshire but does not have 22x as many school districts. Rather, it has 1024 school districts.

So let's talk about the lids and rock. The red states:

Or, if you prefer, these states and territories:

all have what's know as "textbook mandates." It means there are laws or policies at the state-level that allow someone (or a panel or committee) at the state level to tell the rocks in their jar which textbooks to use. These states do not.

(California is technically both. It's complicated.) Education Commission of the States complied a great report that connects each state and territory to the law or policy at play regarding textbook adoption or non-textbook adoption.

When I started toying with the jars and rocks, I didn't have Mr. Henderson in mind, but I do now. The biggest thing I'd want him to understand is that the American system of education isn't this.

It's this.

When we talk education in America, we have to remember we're talking about 19,000 separate systems, separated into 58 different jars - each with their own laws, policies, histories, structures, and culture. Their own superintendent and their own school board. Their own fleet of school buses and person who is responsible for make lunch for all of the little bodies that move through the school hallways. It's a pretty important detail to keep in mind, I think, when we talk about changes in American education.

I'm determined to figure out how to turn all of my pictures into a video that's more accessible to the yoots but it's stopped raining and so I'm going to go for a bike ride on my snazzy new bike.